Microplastics in soil

During of my Bachelor of Science at Unimelb, I took a subject called Science Communication and Employability run by Michael Wheeler and Jen Martin which I loved. One of our assignments was to pick a topics we were interested in and write a blog post about it.

At the time a paper had recently been published detailing the increase in microplastics in the environment, and particularly our oceans, from our clothes. Microplastics were entering the waterways during the washing process which was not effective at trapping the small microplastic particles moving through the sewerage system. (I’ve linked both my blog post and the paper here in case you’re interested).

Since then, it’s become much more widely acknowledged that plastic waste and microplastics are very much present in our environment and as a result, our sewerage systems have been improved to collect microplastics before they enter the waterways.

So, to my surprise, when I spoke to Ian about his masters project last year, I was honestly quite horrified to learn of the extent to which microplastics have now permeated another key ecosystem that we rely on – soil.

Iam Lam, soil scientist, plant collector and all around great human

Ian Lam has completed Bachelor of Agriculture and Masters of Biosciences at the University of Melbourne. Growing up in Hong Kong, Ian originally wanted to be a veterinarian but much like myself, after completing work experience in the form of an internship, shifted his focus to the environment more broadly.

After completing his Bachelor of Agriculture Ian was keen to continue studying and expand his knowledge beyond what he had learned in his Agriculture degree. After meeting with various potential supervisors about his interests, Ian and his masters supervisor Suzie Reichman designed a project to examine microplastic pollution in our soil systems, and specifically how that affects earthworms.

Ian and I sat down last year so he could give me the dirt (pun absolutely intended). I learnt so much in our interview which I hope you’ll find interesting too.

Interview with Ian

Q: Why is this work important and why it hasn’t been done before?

Before 2015 there weren’t any papers on soil microplastics. Microplastic pollution [in soil] is a massive issue. Most bacteria in the soil does not break down plastic. So, for example, a plastic bottle would take around 400-500 years to break down. It persists in our environment for a long time. 79% of all plastic produced since the Industrial Revolution still exists in our environment, persisting in landfills or is mismanaged and spread across our natural environments.

Often when you hear about studies about plastic or micro plastics, it’s always about the ocean or other aquatic environments because there's a lot more standardized techniques for uncovering microplastics in [those] environments.

If you imagine you dig through a pile of soil trying to find plastic - that is a lot harder than just looking at a jar of water going ‘yep, scoop that up’.

It’s estimated that there is 23 times the amount of plastic in soil compared to the oceans, depending on the location and environment but not enough research has been done yet to say for sure. So we know it's bad, but we don't know how bad and what the exact effects are, because it's a very new field of study. There is an increasing number of studies with 8 published by 2020 compared with none in 2015.

We do know that [microplastics] have adverse effects on a lot of soil organisms, specifically related to agriculture, so that can relate directly to human health as well, and a lot of other ecosystems. I think the point is that there needs to be a lot more research done in the field, and a lot is unknown.

Q: Where are these microplastics coming from?

A massive source of microplastics in our soil is actually from our washing machines. Approximately 97% of detected microplastics found in soils are plastic fibres that come directly from synthetic textiles such as our clothes after they’ve been through our washing systems. A lot of [synthetic fibres] are shredded and go straight into our sewage system.

The good thing about our sewage system is that it does a really good job at preventing those microplastics from entering the rest of the waterways and going into our oceans and rivers. But what we do with that waste that gets trapped – what we call biosolids – is we take and use that in agriculture as a form of fertiliser, so all of that plastic is thrown directly into our agricultural soils.

What this means is, in Australia, we eat approximately credit card's worth of microplastics each week. This claim came from a study that has now been peer reviewed and turns out to be largely true as an average. So, a lot of us could be consuming a credit card's worth. Maybe some less, but it is still a lot.

Q: So given the context, what are you doing within that? What does your project look at?

My project is specifically on worms. Worms are keystone species and ecosystem engineers. So, they're very, very, very valuable to our soil ecosystems and just ecosystems in general. They play a huge part in a lot of food chains, and especially in agriculture. One study showed ‘average earthworm presence in agroecosystems leads to a 25% increase in crop yield’. So, yeah, worms are very important and without worms, a lot of ecosystems would collapse and that would be detrimental to our food systems too.

We know that agriculture really relies on earthworms for soil health, and we also know that agricultural soils are one of the biggest sinks of microplastics. So looking at the connection between two, it could be pretty concerning for human health, the health of the environment and the health of these worms specifically.

Nothing's is officially published yet but I can say there is a negative correlation between increased concentrations of microplastics and earthworm survival in concentrations detected in the environment and in our agricultural systems.

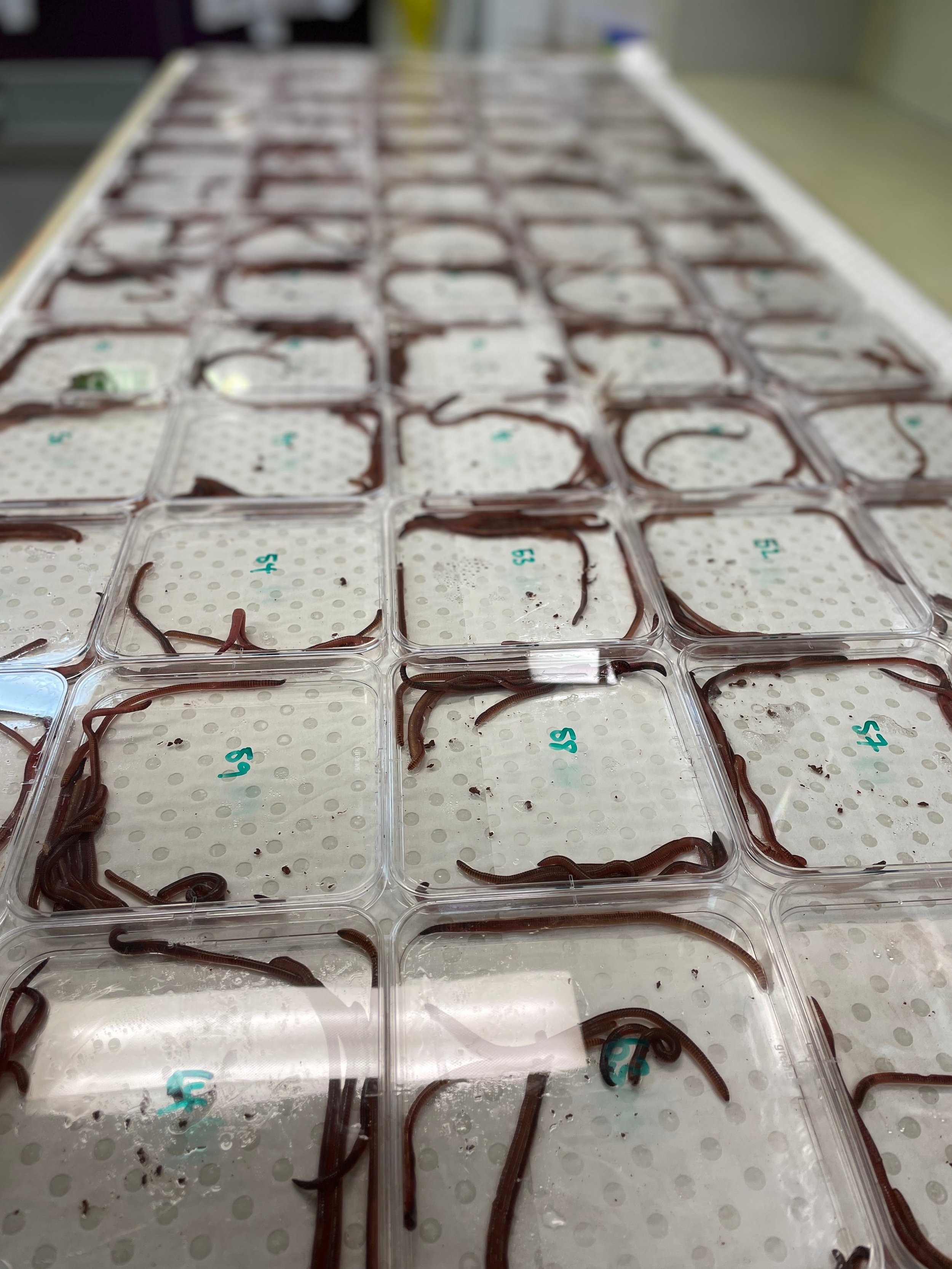

Images from Ian’s research: from left to right: a) earthworms being prepared for the soil microplastic exposure experiment, b) section of polyester yarn and microplastic fibres from the same piece of yarn used in experiments and c) microplastic PET glitter under the microscope

Q: Where to next for your research?

Overall, because there isn't that much research in the field, there definitely would have to be more research for any change to happen [at a policy level]. Policy change would be ideal in terms of finding ways to stop that microplastics from entering the biosolids that we use in agriculture. That would stop a ton of microplastics from entering the environment. In Australia specifically, we use 70% of all the biosolids we create in our agriculture, and that's higher than most of places in the world. So research is pretty important for shifting this norm through education and policy.

Q: How do you keep hope for the future given you’re working on a topic that could be quite depressing?

I think, overall my attitude is as long as I'm trying my best, there's not much else that I can do as an individual.

Obviously, there is always room for improvement, but I think I'm on that right path of trying my best to do good. So I try to give myself slack for just, I guess, being a human on this planet.

Otherwise it’s all just depressing, especially doing research about the environment and climate change. You’d get worn out pretty quickly if you didn't have mechanisms to protect yourself.

Ian via his instagram @myunhealthyplantaddiction

Q: Do you have any practical tips for people reading this and thinking it’s a bit depressing?

A very tangible thing that every individual can try to achieve is buying clothes more sustainably and ethically, but also looking at what it's made out of. If it has a high percentage of plastics, maybe try to avoid it and just try to find natural textile alternatives such as cotton, wool and hemp. Hemp's a great one.

So yeah, more natural textiles. Sometimes you can’t avoid it, so just try your best.

I think it's also a privilege to have the option to ‘go all cotton in my closet’, or use all natural textiles, because they are often more expensive compared to a lot of plastic based clothing. So just try your best and do what’s in the realm of your resources, because what else can we do? In a positive way.

Another one for our health too - we can vacuum more. A recent study in Sydney found that approximately 39% of household dust is made up of microplastics. I mean, it's everywhere. It’s in our blood and in the most remote ecosystems, untouched by mankind. It’s a collective problem rather than individual one and that’s why we’re doing the work, but it doesn't hurt to vacuum a bit more just for our own health.

I guess creating a healthy environment in your home never hurts. Whether related to microplastics specifically or not, things like vacuuming or getting more house plants can make our homes calm places we enjoy being in.

Image from Ian’s instagram @myunhealthyplantaddiction

Ian Lam is one of the kindest people I know, and I want to thank him for his generosity in taking the time to speak to me. The work he and his team are doing is vital for securing our food system as we move into a period of unstable climatic patterns and biodiversity loss. Despite what may seem to be grim research findings, his hope for the future and belief in individual actions to bring change is incredibly comforting.

It reminds me of a quote I associate with my mum growing up but is attributed to Margaret Mead. It rings true in the face of overwhelming need to tackle the climate crisis, “never underestimate the power of a small group of committed people to change the world. In fact, it is the only thing that ever has”.

As Ian says, “just do your best.”

If you’re interested in getting in touch with Ian about his research or love of the environment, you can follow him on instagram @myunhealthyplantaddiction or @ianlamsc, or alternatively find him on LinkedIn.